Ron writes:

The Early Bird Certificate Package casts a long shadow upon the history of the Kenner toy company's involvement with the Star Wars license.

Even those uninitiated into the mysteries of toy collecting are aware of it. "Hey," they'll say, "didn't Kenner offer an empty box for Christmas of 1977? That was pretty wild."

But in case you're clueless, allow me to summarize: Because Kenner's agreement with Fox wasn't signed until the spring of 1977, the company was unable to bring action figures to market for the holiday season of that year. Though they did release a few paper and cardboard items in the fall, action figures had to wait until late winter of 1978.

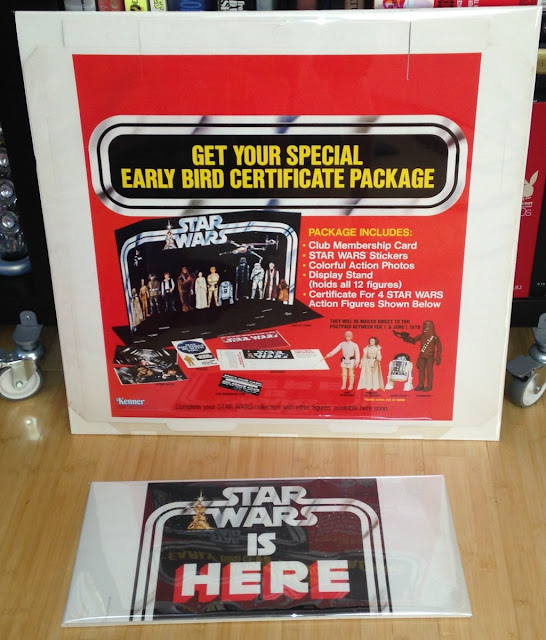

The Early Bird Certificate Package was Kenner's solution to the no-figures-for-Christmas dilemma. A stopgap product, it consisted of a graphical envelope containing a cardboard figure stand and a certificate; the latter could be redeemed by mail for four action figures, to be shipped directly to the consumer at a future date.

"It takes several months to go into production on an item, so we don't even have one to show the buyers," Gerry Dougherty, a Kenner salesman said."But we are offering a gift package that includes a Star Wars display stand, stickers, club membership card and postage-paid mail-order card for a set of four plastic action figures from the movie -- Luke Skywalker, Princess Leia Organa, Chewbacca the Wookie [sic] and the robot R2-D2, registered under the trademark 'Artoo Detoo.'"

"We'll have advertising stressing the early-bird certificate," [he] said, "so children will know what they are getting and won't be disappointed. Then they'll be able to get the whole set later, Darth Vader, See Threepio, Ben (Obi Wan) Kenobi and other characters from the movie."

"I'd rather have something for my kids to play with right away," said a Dallas mother. "Can you imagine their faces on Christmas morning when they unwrap an envelope? They'd be madder than a Wookie [sic]!" [2]

In case retail buyers and consumers had any doubts on that front, Dougherty shamelessly pulled the lever of peer pressure: "It's the be-the-first-on-your-block appeal," he said, adding that "kids will want the real Star Wars item, even if they have to wait."

Retailers, though, were less certain.

Said one quoted in the article: "Children don't really care whether they get the officially licensed product or not. A robot is a robot."

And so the terms of the battle were established: it was licensed versus unlicensed, the Real McCoy versus what I guess I'll call the Counterfeit O'Houlihan.

Kenner's chief adversary in this battle (the Big Chief Counterfeit O'Houlihan) was the Ideal Toy Company, whose S.T.A.R. Team line survived a legal challenge to compete with Star Wars for holiday dollars.

Though the S.T.A.R. Team was comprised of toys that had been released by Ideal in a prior year, it was close enough to Star Wars to tempt retailers with the promise of space-related profits.

Indeed, it was Ideal's products, not Kenner's, that illustrated many articles devoted to holiday gifting for the 1977 season. For an example, see the item pictured above, from the December 8, 1977 issue of The Argus.

Fortunately, a Kenner spokesman was quoted in the piece, and he made a case for the real Star Wars:

We did a lot of thinking before we made the decision to send out a certificate package. But we felt that because of the success of the movie, the child would want the authentic figures. We also decided that if a child receives the certificate package as one of his toys, he will be satisfied, and getting the actual gift later on could extend the feeling of the holiday season.

A couple of messages were communicated here: First, you're buying garbage if you aren't buying the authentic Star Wars. Second, getting your Christmas presents in February isn't weird; it's actually a good thing!

Less sanguine was the lone retailer quoted in the piece: "We feel a child would like to get a gift at Christmas, not a certificate," said a representative of Marshall Field, "unless the parents want to buy a regular gift certificate from our store."

Backing words with action, Marshall Field refused to carry the Early Bird Certificate Package.

How's that for extending the feeling of the holiday season?

Marshall Field wasn't alone.

Per this item, from the December 22, 1977 edition of The Idaho State Journal, an area retailer named Grand Central also opted to avoid the Early Bird Certificate Package. "We chose as a company not to buy the Star Wars toy from Kenner," said the store's manager, ". . . the reason being most people don't want to buy something now and get it four to six months later."

Well, that gripe sounds familiar.

Another retailer quoted in the piece was only slightly more positive.

Keith Groh, Osco Drug store manager, says his outlet has about a dozen of the Star Wars toy certificate boxes in stock, but the item hasn't been a "big thing" for his store. "If anybody wants any of them, we've still got them available," Groh remarked.

In hindsight the retailers who refused to carry the product seem overly stubborn.

But, as I wrote at the start of this piece, upon the release of the Early Bird Certificate Package, it was often seen not as the fun and novel thing that it's taken for today, but as something adjacent to a scam.

I find it hard to criticize retailers for their skepticism. The product probably set a few gears to turning in their minds.

After all, one of the main functions of a store is display of product. People patronize them in order to see the goods, to kick the metaphorical tires. If no goods are displayed, then what's the point of the store? People might as well buy direct from the manufacturer, or through a catalog outfit. In short, the certificate rendered superfluous one of the primary drivers of retail shopping.

There were more immediate concerns as well.

Put yourself in the shoes of the folks at Marshall Field. What happens when a customer who purchases the Early Bird Certificate Package at one of your locations is unhappy with the figures he eventually receives? What does he do? Does he complain to Marshall Field, or to Kenner? In short, by asking retailers to carry these certificates, Kenner was asking them to take their word for it. "Don't worry," they were saying, "the product will be good, and your customers will be happy."

Some just weren't willing to take that bet.

Betty Slaugh, owner of the Michigan-based Toy Village, certainly wasn't.

According to the November 30, 1977 edition of The Lansing State Journal, Ms. Slaugh "want[ed] no part of the gift certificate scheme," adding that "the manufacturer shouldn't have the right to pre-sell a toy."

It's not like Kenner didn't take the time to examine the hurdles faced by their product.

The gift certificate . . . was tested with several thousand parents in four cities, including Cincinnati, and then with retailers. The response, a spokesman said, "was favorable.""We did it," he said, "as a consumer service."

Definitely not, says Vickie Oldenham."They would not be happy with that on Christmas morning." Mrs. Oldenham said Wednesday as she stood before a Star Wars "early-bird" certificate display in a SouthPark shopping center toy store.Her three children . . . "would[n't] want those things under the tree."

Claudette Edge, manager of the Jack and Jill toy store at SouthPark, takes a dim view of the whole thing."All we're actually selling is a piece of paper," she said. "This is unreal."Parents aren't entranced with the idea. The reaction is nil. Only a real broadminded mother in total command of her household will go along with this."

"We're selling them but people don't like them," explains Ron Middleton, manager of Circus World at the Six Flags Mall. "The main feedback we get is that there will be a lot of unhappy faces on the kids when they get up on Christmas morning and there's nothing under the tree.

"The kids aren't real impressed with them, either. I could probably count the number of kits we sell in one week on both hands."

Middleton said that he even transferred half his stock to another shop in the chain in Dallas because they weren't selling that good and that particular store didn't have the kits in stock.

Ouch.

Somewhat more positive was this take, from a retailer who'd evidently taken fewer grouch pills that morning -- though he still claimed that other Star Wars items (the puzzles, maybe?) had been more popular than the Early Bird Certificate Package.

Over at Toys by Roy in the Forum 303 Shopping Mall, manager Bob Klem also reports that sales of the pre-sell kits are slow compared to the other items modeled after the famous science fiction fantasy flick.

"There was a lot of speculation when the kits first came out, but people have been buying them. I've got about one-third of my stock left," Klem said.

One-third of stock remaining four days prior to Christmas?

Well, I guess it could have been worse . . .

This is the first article we've discussed that specifically alludes to low sales. But as the following item will prove, sales problems were a common theme of news reports concerning the Early Bird Certificate Package.

Though it was published in the December 19, 1977 edition of The Bradford Era, it was an AP item, meaning that versions of it ran in papers across the country.

Of the three previously discussed articles, which do you reckon has the biggest bummer of a headline?

- Star Wars Toys -- In 2525?

- IOU's Unpopular

- Star Wars 'promise' not a big seller

It's hard to beat "IOU's Unpopular" for blunt potency.

Still, I have to give the Jerky Journalism Prize to the third headline with its scare quotes surrounding "promise." It makes me think of that shot in Citizen Kane.

Like the reporter from the Arlington Citizen Journal, the AP claimed that retailers were disappointed with the Early Bird Certificate Package.

With less than a week until Christmas, the kits are getting a cold reception in [the Philadelphia] area.

"They aren't going too well," admitted John Kreemer, toys merchandising manager for the Strawbridge and Clothier department store here.

"It surprised us."

Well, since Mr. Kreemer raised the topic of surprises . . . do you want to know what in the article surprised me?

The Sox Pot.

If you read the whole thing, you undoubtedly noted the below bit concerning the Sox Pot.

One retail oddity that seems to be getting the business this season is the "Sox Pot," a lucite plant pot, packed with seeds and four pairs of argyle socks.

Bob Knighton, a hosiery buyer for Gimbels, said 2,000 Sox Pots have been sold at $12 each in the chain's downtown department store alone.

"It's going to turn out to be the item of the season," he beamed.

Does Bob seem a touch enthusiastic?

Let's agree to give him a pass. How often does the hosiery buyer get to gloat?

I was a little thrown by the article's description of the Sox Pot, not to mention its reputation for "getting the business," so I had to prove to myself that it actually existed.

As the above ad demonstrates, it did indeed exist. And it did indeed consist of "four pairs of sox in a pot with free seeds to plant."

Anyway, if you're at Kenner and you're reading this AP article, I gotta imagine you're asking yourself how in the hell your big new product just got upstaged by the f%@king Sox Pot.

Come to think of it, is "Sox Pot" a play on "sexpot"? I really just have so many questions . . .

* * *

I think we established a few things with this review. But the main thing we established is that the Early Bird Certificate Package was controversial.

Press coverage skewed heavily negative during the fall of 1977, and the negativity continued right up until Christmas, despite Kenner's efforts to position the product in the best possible light. Some stores refused to carry it, and many reported poor sales. Perhaps most importantly, at least some consumers were outraged by it.

But was it commercially successful? Did it succeed at "getting the business"?

Though it betrays some vestiges of the prior autumn's negativity, including the complaint of a seven-year-old who claims he had to "wait too long" to receive his Early Bird figures, it also includes Bernie Loomis' estimation that "several hundred thousand" figure sets had been shipped to consumers.

Perhaps more importantly, the article positions the Early Bird Certificate Package as the kickoff product of a grand and transformative toy line -- which is more or less how it's viewed today.

But let's return to the sales stuff.

A sales volume of several hundred thousand units sounds pretty respectable.

But I do wonder if Kenner hadn't hoped for a response that was a bit more robust.

My doubts are at least somewhat validated by this piece, from The Herald News of November 15, 1977.

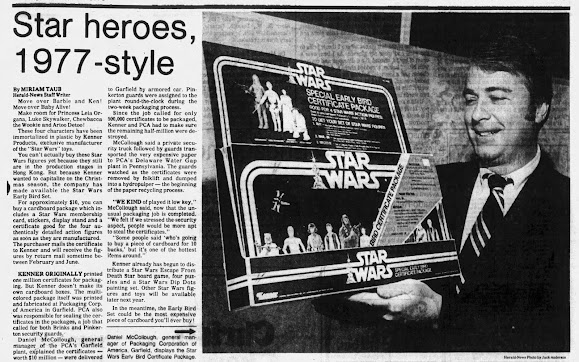

It focuses on Packaging Corp. of America (PCA), the outfit based in Garfield, New Jersey that was commissioned by Kenner to print and assemble the Early Bird Certificate Package.

The article is great. Not only does it include a photo that will stoke the delight of any collector of store displays, it provides information that (as far as I know) has never been presented to the toy collecting community.

Apparently, the handling of the freshly printed Early Bird Certificates was a high-security procedure:

Daniel McCollough, general manager of the PCA's Garfield plant, explained that the certificates -- worth $10 million -- were delivered to Garfield by armored car. Pinkerton guards were assigned to the plant round-the-clock during the two-week packaging process.

Pinkertons solemnly guarding pallets stacked with pristine Early Bird Certificates! What an image!

But the article also provides some interesting information regarding production numbers and, potentially, sales expectations:

Since the job called for only 500,000 certificates to be packaged, Kenner and PCA had to make sure the remaining half-million were destroyed.

McCullough said a private security truck followed by guards transported the very expensive paper to PCA's Delaware Water Gap plant in Pennsylvania. The guards watched as the certificates were removed by forklift and dumped into a hydropulper -- the beginning of the paper recycling process.

So, 500,000 Certificates were packaged for distribution to retailers. That jibes with Loomis' claim of "several hundred thousand" sold.

But half of the number printed (i.e., 500,000) were pulped.

Was the destruction due to lack of orders on the part of wholesale buyers?

That's my suspicion. I think Kenner hoped to sell up to one million Certificates, but only managed half of that.

* * *

Ultimately, it didn't matter a whole lot if Kenner didn't sell a million Early Bird Certificate Packages during the holiday season of 1977. The Star Wars line was a success, and those parents who didn't buy Certificates for the holidays probably bought the figures for their kids when they hit stores in February and March of the following year.

Either way, Kenner sold figures.

As for the bad publicity . . . well, it was free advertising, right?

Maybe all that scandal actually helped in the long run, because it gave the newly minted Star Wars line a hook, something for folks to remember it by. Even if you weren't convinced by Kenner's marketing, you read those news stories and you knew that Star Wars figures were coming, were in fact just around the corner. And that awareness was valuable to the people selling Star Wars, namely Kenner.

It's been decades since the furor over the Early Bird Certificate package subsided. Today, all the major toy companies sell direct to the consumer. In doing so they don't even bother to sell a certificate at retail; retail is entirely outside of the equation. Sometimes they won't even manufacture an item if a sufficient number of people fail to pay for it beforehand.

Is this a positive or negative development? I don't know. But I do know the Early Bird Certificate Package played a part in laying the groundwork for it.

Notes:

[1] If you're bugged by the low quality of the photograph, consider giving me a break. I took it almost 25 years ago, using a digital camera that makes your iPhone camera look like the camera on the Web Space Telescope. You're lucky you can read the plaque at all. Fortunately, Loomis' write-up on the organization's website is more readable -- and also mentions the Early Bird promotion.

[2] The quotes it this article strike me as artificial. The Kenner spokesman's use of marketing terms (e.g., "Artoo Detoo") have the ring of written rather than spoken words. And part of me doesn't buy the mother's quip about her kids getting madder than a Wookiee. I suspect the article's quotes were cobbled together from written correspondence and/or partly fabricated.