Sunday, May 22, 2022

'Chive Cast 122 - Lumat's Ewok Junk

Wednesday, May 18, 2022

Turn On Your Force Light: The Great Knock-Off Lightsaber Wave of 1977-78

Ron writes:

Intro

If you've read my other articles, especially this one, you know that Kenner, the principal Star Wars toy licensee, was in a bit of a pickle come late 1977.

Though Star Wars was a smash hit, Kenner wasn't able to meet the demand that it generated among the toy buying public. This wasn't Kenner's fault: The company had only acquired the toy license that spring, just before the movie hit theaters, and toy development takes time -- over a year in some cases.

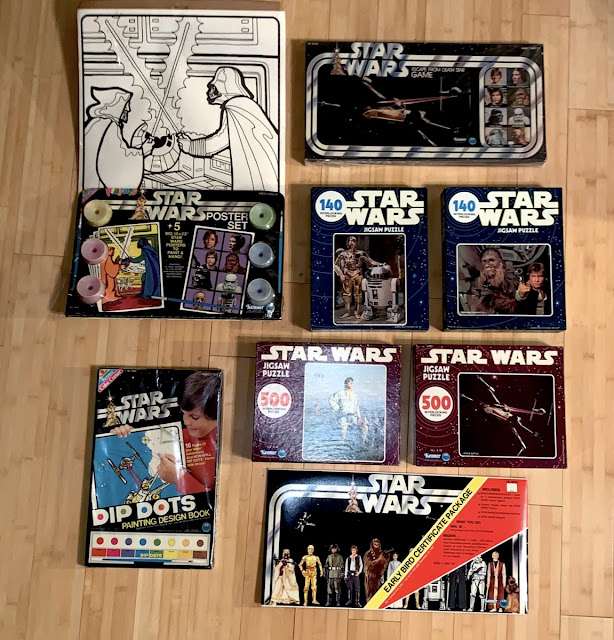

And so the Cincinnati-based company entered the holiday season with a lineup boasting only a few Star Wars products. Eight to be precise: two coloring sets, four puzzles, a board game, and the novel Early Bird Certificate Package.

The last was a glorified gift certificate that children could redeem for action figures -- to be delivered after a few months of agonized waiting. Because it asked consumers to pay for products that didn't even exist, it generated quite a bit of controversy in the press.

Obviously, a lot of iconic Star Wars paraphernalia was missing from the above list. Spaceships, blasters, and droids were nowhere to be found.

Neither were lightsabers.

Of all the gadgetry in Star Wars, nothing was as likely to captivate the imagination of a child as the glowing weapon of the Jedi Knights. In 1977, as the movie wowed audiences across the United States, kids everywhere supplemented their Star Wars roleplaying adventures with sticks, cardboard wrapping paper tubes, and broom handles. Anything that could compensate for the lack of a licensed lightsaber toy.

But these were poor substitutes for a proper lightsaber. For one thing, they didn't glow. For another, they were dangerous. Have you ever been whacked with a broom handle? It was clear that something better was needed.

Fortunately, Americans are plucky, entrepreneurial, and (perhaps most crucially) somewhat dismissive of copyright law. In the waning days of 1977, they rose to the challenge, and marketed their own damn lightsabers.

This is the story of their efforts.

* * *

John Joyce Has a Bright Idea

Selling for $5.98, the toy consists of nothing more than a flashlight with a long plastic tube attached to reflect the light.

I think they're really neat. I just like to take them out in the snow and swing them around or whatever.

The Force Beam: Capitalizing on the Star Wars Mystique

|

| Yes, that's some weirdo dressed as Darth Vader in this (very cool) vintage toy store photo |

[Darth] Vader, [Luke] Skywalker and the rest of the cast . . . won't be around this season. Not exactly that is . . . [but] there are some amazingly close imitations of "Star Wars" toys already on the market. Remember the weapon of the Jedi Knights, that nifty little glowing sword with the beam of light?Well, Burdines' toy department is carrying something called "The Force Beam" ($7.99) consisting of a flashlight with a plastic tube attached.

The season is not without its duds. And surprisingly, two flops are based on the hit movie Star Wars.One is a $7 plastic wand called a "force beam," and another is nothing more than a brightly-colored package with a gift certificate enclosed."You send the certificate in and sometime between January and June they send you back three or four Star Wars dolls," says Karen MacLean. "I guess they wanted to sell them for Christmas but the dolls weren't ready yet. Anyway, neither the force beam nor the gift certificates sold very well."

Hey, Karen, it's 2022 and the Early Bird Certificate Package is worth thousands while those anatomically accurate baby dolls you like so much are just as creepy as ever.

But probably nothing demonstrates the popularity of the Force Beam quite so well as the letters that kids wrote to Santa in the fall of 1977.

Kansas resident (and apparent Trekkie) Mike Townley didn't bother asking Santa for any of Kenner's 1977 products.

But he did ask for a Force Beam.

At the office of the local paper in Cazenovia, New York, the Force Beam generated confusion and a call to the local toy store.

Sneaking a look at the second graders' letters to Santa published in this issue, we were baffled by requests for "fores bemes." But our resourceful staff telephoned the toy department of a department store and the mystery was solved. FORCE BEAM is the name, and it's part of the Star Wars mystique.

Speaking of mystique, based on this item, from the December 23, 1977 edition of the Naugatuck Daily News, even some celebrities received the Force Beam for the holidays:

Boston Pops conductor Arthur Fiedler breaks into laughter as he is presented what appears to be an oversized baton from a surprise visitor during a Christmas Show at Symphony Hall. The gift from Santa is a new toy on the market called a "Force Beam" taken from the movie Star Wars. The toy is like a giant flashlight and lights up. Man playing Santa Claus is unidentified.

Hey, jerky caption-writer guy, the man dressed as Santa isn't unidentified. He's, uh, Santa. Jeez.

Anyway, either Santa had so many Force Beams on hand that he was just handing them out indiscriminately, or the marketing department of Jack A. Levin and Associates was working overtime garnering press coverage for their prize product.

I can almost hear their marketing guy now: "Fiedler is a big get!"

In case you're wondering, the Force Beam's appeal wasn't limited to the holiday season of 1977; it competed with licensed Star Wars merchandise into the 1980s.

And here it is being marketed as a costume accessory for Halloween 1980, at a price point considerably below its $7-$8 peak.

Well, I think we've established that the Force Beam was a success. And, naturally, success breeds imitation. As we'll see, a bevy of similar products surfed in the Force Beam's wake, most of them using flashlights as their principal component.

* * *

Flashlight Wars: Force Beam Imitators

As we've discussed, the key component of both the Star Force Ray and the Force Beam was a red Eveready flashlight. Likely purchased in bulk, the sales must have enriched Eveready nearly as much as the sabers' producers. It's not often someone tries to corner the flashlight market.

The Space Sword, produced by Hanstai International of Sante Fe Springs, California, was identical in most respects to the Force Beam. But it appears to have utilized a different brand of flashlight.

Though not much is known about this product, it's clear Hanstai knew their market: The logo and the "Force is with you" slogan left little doubt as to which space franchise it was referencing.

A faux saber marketed by the New York-based Durham Industries utilized yet another brand of flashlight.

The base of their Star Beam reveals that it was manufactured by BMG. The conical collar piece connecting the hilt and the blade may have been custom manufactured for the product.

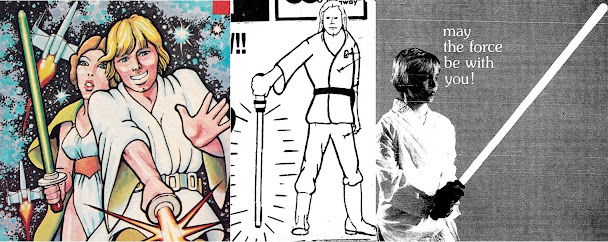

The Star Beam, like the Force Beam, came in red, white, and green variants. The graphical wrapper that adorned the product depicted a boy dressed as Luke Skywalker.

All of the above ads for the Star Beam date from the early part of 1978, leading me to believe that Durham was late to the game with their product, and mostly missed the 1977 holiday season. It may be that the news stories related to the Christmas success of the Force Beam (and perhaps even the Star Force Ray) inspired Durham to rush a similar product to market.

Similar to the Star Beam in that it utilized a BMG flashlight and a conical collar piece was the very peculiar Laser Light.

I call it peculiar because it was -- surprisingly -- marketed to magicians.

Uncle Owen did call Obi-Wan a wizard, so maybe it's actually not all that surprising?

The Star Beam was sold under the imprimatur of Peter Lee Gensemer, whose Sophisticated Sorcery operated out of Medina, Ohio.

Do people still do magic these days? When I was young it was a pretty common: Every kid had an oddball friend whose hobby was magic, and magicians were popular entertainers at birthday parties, school functions, and the like. Now I rarely hear about it, and I suspect it's pretty uncommon that a young person takes up magic as a hobby. Maybe our lives are so filled with semi-magical pieces of technology that analog magic has become superfluous. I think I like the old magic better.

Magic played no part in Funstuf's Space Sword, just good old fashioned ingenuity.

Presumably in order to save on costs, Funstuf eschewed the flashlight entirely, opting instead for a novel design that was all tube. In place of a proper hilt was a sticker bearing the name of the toy.

The instructions and an apparently hand-rigged battery assembly were housed in the lower portion of the tube. Pretty clever!

Advertising for the Space Sword was clustered in the New York area, causing me to suspect it was an East Coast thing. The above ads date from 1977 (left) and 1979 (right), suggesting that the product's sales window was relatively wide -- though by the time '79 rolled around it was selling for a measly 50 cents.

With all of these unlicensed lightsabers floating around in '77 and '78, you may be wondering how Kenner and Lucasfilm responded. Did they take legal action? I think we can be sure they at least considered it.

Lucasfilm was certainly aware of the problem. As a representative of the company told Bananas magazine:

I was walking in a department store one day, and there they were -- laser swords. I couldn't believe my eyes. They were stolen from us and marketed without a license.

The toy known as the Light Beam offers an additional peak inside the official reaction to the great faux saber wave of the late '70s.

Consisting of a tube affixed to a red flashlight, the Light Beam resembled the Force Beam in most respects. It was even marketed, like the Force Beam, out of Los Angeles. In this case by two companies: Moon-Lite and Hotline.

This item, from the collection of Gus Lopez, shows that Kenner's legal department queried Lucasfilm about the legality of the Light Beam.

Interestingly, this occurred in 1982, several years after the Light Beam hit the market -- and probably well past the period of time during which it was a significant seller. The delay suggests that Lucasfilm and Kenner may have been unable to keep up with the flood of these products, let alone respond to them in a timely fashion.

These ads, from the same SoCal retailer, both date from late 1978, suggesting that the Light Beam was a later addition to the family of faux sabers.

Given its similarity to the Force Beam and its SoCal derivation, it's possible the Light Beam was the result of an attempt on the part of the producers of the Force Beam to rebrand and thereby stay one step ahead of legal complications. If true, that might also explain the attribution of the Light Beam to multiple manufacturers. [1]

We've seen a lot of references to the Los Angeles area. For some reason, it was a hotbed of faux saber activity.

Which brings us to my favorite of all of these products.

* * *

Adventuring with the Soldiers of Light: The SST Lazer Sword

Whereas the faux sabers discussed above were all sold either sans packaging or with very rudimentary packaging elements, the SST Lazer Sword was different: It came in an impressive graphical box. That box communicated the idea that it was special. It also gave the impression that the product was something more than just another flashlight rigged out with a plastic tube.

While Kenner typically featured innocuous and often goofy-looking children on their toy packaging, SST took a different tack: The package for the Lazer Sword featured the coolest, most dangerous looking kid in America.

Seriously, David Bowie would ask for this kid's autograph.

In addition to a Lazer Sword, he (or she?) probably had a switchblade or maybe even ninja stars.

SST's PR folks must have been working overtime in the Golden State: Up north, the Oakland Tribune ran a story about Star Wars toys that -- like the article in the Fresno Bee -- pictured no official Star Wars toys, but did picture the SST Lazer Sword. It was shown in the hand of one James Duncan, who looked as though he was about to go to war with that thing and take no prisoners.

The relevant portion of the article reads:

The Lazer Sword, a three-foot plastic column beaming light from a flashlight-like handle, has been popular since reaching local stores in October. Manufactured by Super Sonic Toys, the light saber imitation sells for $8 and under.

But, perhaps due to shortages in the supply of these suddenly in-demand implements, it could also be found in varieties utilizing flashlights produced by Burgess. Above you see models built on blue and black Burgess flashlights.

The instructions were included in the Lazer Sword's Basic Manual, which is my favorite thing related to the product. As the cover warns, its contents were confidential to all but the anointed Soldiers of Light, who I guess were like intergalactic Stone Cutters or something.

As silly as the manual is, you have to appreciate its ambition: It was a pretty savvy attempt by SST to nurture an immersive play experience. It also established an ecosystem of ancillary merchandise.

They travel from planet to planet, bringing peace. When they find evil, they end it. When they find danger, they overcome it. When they find injustice, they set things right. For hundreds of years these brave men and women have protected the people of Space.They are the Soldiers of Light.

I mean, do these guys sound unbearable or what?

Kids who received the SST Lazer Sword surely experienced FOMO upon realizing they'd never be true Soldiers of Light without first acquiring the official Lazer Fighter uniform and scabbard.

The former looks to be a repurposed karate getup, the latter a plastic cup.

To inspire the imaginations of children, SST (through Marquise Enterprises) offered Adventures of the Soldiers of Light, which contained 20 fictional stories, all of them probably better than Splinter of the Mind's Eye.

I think we can safely assume the stories included plenty of tie-ins to salable merchandise.

There was even a fan club with its own newsletter.

Does anyone reading this have one of these Lazer Fighter posters? I'd love to see one. The image used on the poster pictured on the right was also offered on a t-shirt.

Advertising for the Lazer Sword was clustered in the fall of 1977, though stock was still available through some retailers into the summer of the following year.

The product was widely available: I've documented ads from locations on the two coasts, in the Midwest, and New England.

Kids all over the country loved the Lazer Sword.

* * *

Outro

Are you tired of looking at knock-off lightsaber toys?

I am.

I think that's a sign that it's time to wrap this up.

In doing so I don't mean to suggest that we've exhausted the subject. Other knock-off lightsaber toys were released during the period of 1977-78. Collectors will probably be documenting them forever.

They'll probably also continue documenting products, like the glow-in-the-dark Space Sword, that were merely lightsaberish.

Released by Toy Box Inc., the Space Sword was widely sold in both the U.S. and Canada during the summer of 1978, often being advertised beside licensed Star Wars product. There was even a matching shield.

But by the second quarter of '78, Kenner had caught up to Toy Box and the other DIY innovators.

The company's official lightsaber toy utilized a familiar element, a hilt that was basically a flashlight.

But its blade was inflatable, composed of limp vinyl rather than rigid plastic. [3]

In an apparent acknowledgement of its own impotence, it shipped with a dedicated repair kit.

Was Kenner's toy an improvement on the sturdy simplicity of the Force Beam? Was its authorized connection to the Jedi Knights enough to make fans of the SST Lazer Sword forget the Soldiers of Light?

Maybe.

We like authorization because it guarantees the fulfillment of our baseline expectations. We dislike it because it limits our options -- and perhaps our imaginations.

Life is all about tradeoffs.

Notes

[1] I own three sabers (in red, green, and white) that are identical to the Force Beam in all but their branding. In fact, they feature no branding at all, consisting of nothing more than Eveready flashlights with plastic beams attached to them. Their existence may be an additional indication that the producers of the Force Beam mixed up brands and manufacturers as they attempted to avoid legal action.

[2] Though the article mentions the battery-powered toothbrush as being planned for Kenner's fall 1977 lineup, that product was neither included on Kenner's wholesale order form nor featured in the company's 1977 Star Wars catalog. On top of that, I've never seen it in an early advertisement. I believe it was put off until early 1978.

[3] Maybe Kenner deserved points for innovation? Only if you aren't aware of the knock-off inflatable saber released in 1977 by an outfit called Skyline, Incorporated.

Thanks to Yehuda Kleinman for providing a few Lazer Sword photos. Thanks to Eddie for providing the vintage store photo. Thanks to Steve Sansweet for permitting the use of the photos of the rare Star Force Ray, which is a part of the incredible Rancho Obi-Wan collection. Extra special thanks to Pete Vilmur, without whose assistance and photographs this article in its final form would not have been possible.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)