Tommy writes:

Back in the days before text messages and Facebook IMs, people kept in contact with distant family and friends through magical things called "letters." If you were willing to spend a few dollars, you could even buy a special type of letter, called a Star Wars greeting card, which came pre-printed with an image of Star Wars characters and a generic greeting inside, because no one ever knew what to write in them.

Okay, I'm kidding... kinda. While perhaps not as popular as they once were, greeting cards are still a huge business and I think everyone has sent or received them at one time or another. There have been dozens and dozens of Star Wars greeting cards over the years, released by a number of different companies. Funny cards, meaningful cards, romantic cards, you name it. Released for every holiday and occasion, in a rainbow of colors.

As with all things however, these cards did not spring fully-formed onto store shelves. They had to be created by artists and printing professionals, all of whom were trying to make something that you'd want to send out to your loved one as an expression of the sentiment you were feeling. They needed to write your own words for you and present them in a way that made you want to pay them for it. As such, the people responsible for these cards needed to be at the top of their game, and the process they used to create the final cards is a complex one.

With that in mind, I now present the complete design process of the vintage Star Wars greeting cards released by Drawing Board, showing (almost) every stage of how they were created.

|

| Specification Sheet |

Our greeting card begins here, with this creative specification sheet dated October 1978, which seems to amount to a work order. It is the management of Drawing Board telling its artist what to paint and why. In this case, they are telling Mary Grace (the artist responsible for many of the vintage Star Wars greeting cards) that she needs to paint a C-3PO and R2-D2 card. They provide her the size it needs to be and the type of stock the final card will be printed on.

Now, I'm assuming that she would need to present them with some kind of thumbnail sketch of her idea as to pose and layout, but that seems to have been done more in a meeting setting rather than in a formal step. I have never seen any kind of rough or preliminary for these cards, despite there being examples of every other stage around. As such, I assume it's either that the approval step was more casual or perhaps the artist simply didn't paint that way and instead chose to present her bosses the finished art for their approval.

|

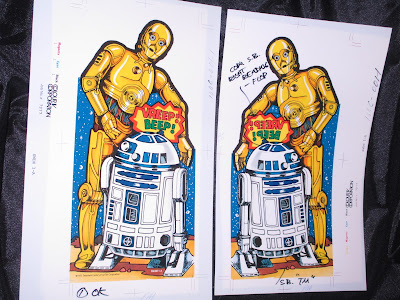

| Original art with clear transparency in place |

Once the artist has the specification sheet in hand, they can begin to work on the actual art for the cardback. Here, the artist has rendered a very nice image of R2 and 3PO.

|

| Original art with the clear transparency removed |

|

| Mechanical layouts for the back and interior of the card |

The artwork is not the only thing printed on the card however, so the printer needs to produce these mechanicals for the inside and back of the card. You can think think of them as a layout for the design, featuring elements hand-pasted onto the board and the proposed outline of the finished card once its die-cut penciled in, showing where everything needs to go. This helps guide the printer and ensues that there aren't any mistakes when the card goes to press, since it's already all planned out.

You can see that our card is destined to be a "get well" card, and it's at this stage that the greeting inside is finalized. On some cards, this decision was made on the design specification stage, but with this particular example, it appears they decided the greeting after the art was already finalized.

We are missing a stage here. The printer would use the art to create films/separation sheets, which are transparent sheets showing where each color on the finished card needs to go. So, for example, there would be a sheet simply showing everything that's blue on the card and nothing else, and a sheet showing everything that's yellow, and so on. The 4-color printing process needs to lay down each color in turn, producing the final image once the card went to press, so each color is planned separately. The films create the plates, which did the actual printing. None of the films have ever turned up however.

|

| Blueline (front) |

Once the films are created, they are proofed using a blueline. A more inexpensive form of proofing than Cromalins, the blueline is simply showing all of the colors on the card in various shades of blue. The primary purpose of the blueline would be to check things like registration and to ensure that the films do not contain imperfections or create bleed. In other words, it is used to spot big problems. You can see that the printer has circled a number of issues with the films, indicating what needs to be fixed before the card goes to press.

|

| Blueline (back) |

The blueline is actually double-sided, the back showing what the interior of the card will look like.

|

| Cromalin Mock-up |

This is an odd stage and I'm not entirely certain what's going on here. For ease of identification, I'm going to call it a Cromalin mock-up, but that's not actually the purpose it's serving. The printer has created a Cromalin of the art (a term I will define in a moment), but they've done it in two pieces again.

|

| Cromalin mock-up without overlay |

The exact purpose of the stage remains a bit of a mystery though, in that there is also a tracing paper overlay, showing odd blocks penciled onto it. I believe that it has something to do with translating the 2D image onto the embossing dies, as other examples I have of this stage for other cards are marked as being "Multi-Level Embossing Die SS," but I'm not sure what that means. I would guess that they wanted to see the black lines and the colors as two different elements, since the black lines would delineate which details would need to be raised on the final card and which would remain flat.

If you want to hazard a guess as to the actual purpose though, feel free to drop me a line in the comments section.

|

| Cromalins for the front of the card |

|

| Cromalin for front and back of card |

Cromalins:

Once their mock-up stage has served whatever purpose they had for it, the printer can start to finalize color correction and continue the proofing process. As we saw in my article about creating an action figure, Cromalins allow the printer to do color management and correction, in addition to simply checking that everything is as it should be. In other words, they are used to spot smaller issues with the films than would be evident on the blueline. Cromalins are one-sided and printed on slick photo-like paper, which allows for very vibrant colors. In stark contrast to the cheaper bluelines, Cromalins are expensive to produce.

Here we can see they started out printing just the front of the cards, even making a mistake and printing one of them as a mirror image. A later example shows the front and back of the card.

Once the Cromalins were used to proof the films, the final printing plates would be created and the printing process could begin. None of the plates used to print the Star Wars greeting cards have ever turned up.

|

| Proof |

Once the printing plate was created, they could start producing proofs to test them. You can see the color bars at the top, used by the printer to keep track of the colors and to make sure all of them are printing correctly. He has written in some notes on the colors, indicating changes to the intensity which need to be made before the final cards are produced.

This proof is essentially a card which was never die-cut, although the message inside (which Drawing Board calls "the sentiment") is not printed on the reverse of this sheet. The printer has written in a notation that the sentiment is on the Delux (which I assume is the Cromalin stage) however and needs to be checked before the card goes to press.

|

| Embossing tests |

It should be remembered that the card still needed to be embossed however, so that all of the details of the droids would be three-dimensional.

Typically, the embossing process involves the creation of dies showing the image of the final card and the desired 3D details. On one of the die, the details are raised and on the other, they are recessed. These sheets of paper were then pressed between the dies as a test. The raised details on one die pushed the paper into the cavities of the other die, creating the embossed effect. Once the samples were approved, this process could be repeated and production of the embossed cards commenced.

Sadly, the embossing dies themselves have never turned up.

Die-Cutting:

The last stage in our process would be to run our printed and embossed cards through a die-cutter. The process (sometimes called "dinking") is essentially like an ordinary office hole punch, but instead of being round, in this case it's shaped like 3PO and R2.

The uncut cards go into the machine, where a rotary die (a cylinder with a raised cutting edge in the shape of the outline we want) is slowly turning. The paper passes beneath the turning rotary die, and the shaped blade is pressed down onto the card, cutting away the excess paper like a cookie cutter as it rolls over the card. Since the only thing touching the cardstock is the sharp edge of the die, the embossing is not affected by the process.

Technically, I suppose you could do the dinking (and yes, I'm using that term simply because it makes me giggle like a schoolgirl) before the embossing, but given the fact that the embossing samples are not die-cut, that doesn't appear to be how Drawing Board did things. That's purely conjectural on my part though, I've never confirmed it with anyone at the company.

In either case, the rotary dies used in the creation of the vintage Star Wars greeting cards have never turned up.

|

| Company storage envelope |

The various stages of this card were transported around the company in a special envelope, showing what the card looked like and giving its internal product number. This ensured that everything stayed together, should the company ever need it again, and that none of it was lost as it was passed between departments during the production process.

|

| Final greeting card |

Here we see the end result, the final embossed and die-cut C-3PO and R2 get well card.

|

| Mobile mechanical |

It should also be noted that Drawing Board was so happy with the design of this particular card, that they used it as one of the danglers on their display mobile, which hung in stores to advertise their cards. Here we see a mechanical for the project, telling the printer how to alter the greeting card so that it could be used for a new purpose.

|

| Drawing Board greeting card store display mobile |

Here's the final mobile, showing the recycled image from this card.

The other cards on the mobile went through the exact same process as this card. In fact, I have the matching production run of the Stormtrooper card. Drawing Board was very good at saving their work and I've managed to collect pre-production series of several different greeting cards now and am always looking for more.

And so, there you have it. Everything that goes into making a greeting card. As you can see, it's not a simple process and it requires a lot of different stages to get right. Next time you walk past racks of greeting cards in a store, just think of the hundreds of man-hours represented in those simple folded pieces of paper.

Thanks to Tracey Hamilton and Ron Salvatore for helping me to figure out what some of these stages are, and to Todd Chamberlain for the image of the mobile.

No comments:

Post a Comment